A legal analysis of child protection legislation in Belgium

ECPAT International’s latest report looks at the sexual exploitation of Boys in Belgium by analysing current child protection legislation in the country. It reveals how gaps in certain Belgian laws put children, including boys, at risk of sexual exploitation.

ECPAT’s sixth report under the Global Boys Initiative, following Pakistan, Hungary, Thailand, South Korea, and Sri Lanka, identifies gaps in Belgian legislation and outlines recommendations for improvement. Together with ECPAT Belgium, we conducted ground-breaking research into the sexual exploitation of boys in Belgium during 2021.

Our research included a comprehensive analysis of the Belgian legal framework which addresses various crimes related to the sexual exploitation and abuse of children, with a focus on boys. The legislative analysis used a standard checklist including approximately 120 points and sub-points that was created by ECPAT International for the Global Boys Initiative.

How do Belgian laws criminalise the sexual exploitation of children?

The Belgian Criminal Code contain several provisions that criminalise the sexual penetration of minors aged below 16.

Encouragingly, these provisions are gender-neutral, meaning that boys and girls will be afforded the same rights and protection. However, girls benefit from additional protection and attention provided by several international treaties Belgium has ratified, such as the Istanbul Convention.

Belgian law stipulates that while minors aged between 14 and 16 may consent to sexual intercourse, it will still be criminalised, albeit on a lighter charge. A concerning issue with this law lies in non-consensual cases, such as child sexual exploitation and abuse, where the burden of proof in determining the lack of consent falls on the child.

Shifting the onus onto the victim can be highly detrimental and potentially lead to revictimisation of the child, exacerbating their trauma, and may deter them from reporting due to fear of reprisal or not being believed.

Trafficking—the most documented form of child sexual exploitation in Belgium

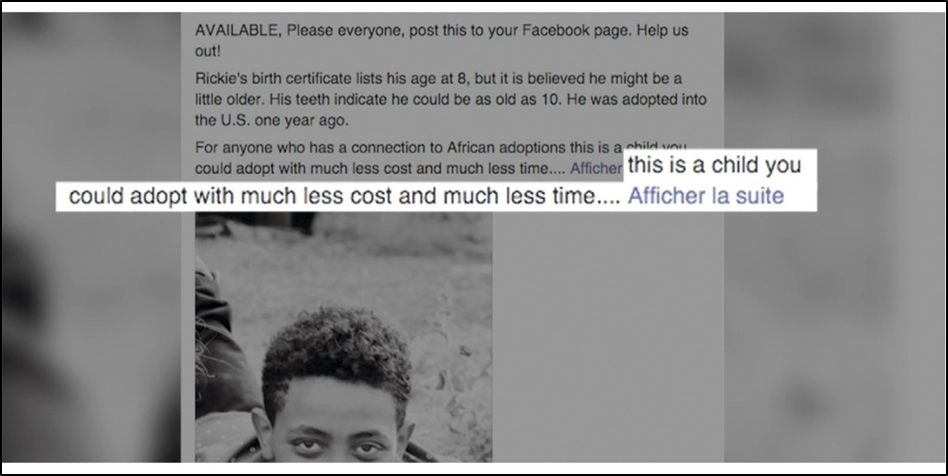

Boys can be groomed through a wide range of in-person and online platforms, and trafficked or sold for sexual exploitation.

Myria’s 2020 annual report on the trafficking and smuggling of human beings found that over 300 human trafficking offences were recorded by the Belgian police in 2019, more than half of which were for sexual exploitation [1].

Although trafficking is the most documented form of child sexual exploitation in Belgium, there is no centralised database that provides disaggregated and comparable data—particularly by gender. Such data is critical to understand how many boys and girls are affected by issues of child trafficking for sexual exploitation purposes, and what resources need to be allocated to better prevent and respond to these issues throughout the country.

Belgium’s national legislation effectively criminalises the trafficking of children for sexual purposes in line with international standards. However, it does not prohibit the sale of children for sexual purposes, leaving children especially vulnerable in such situations.

Are Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) laws comprehensive enough?

The sexual exploitation of boys is not limited to the physical environment—they can also be exploited in the online environment for the production of child sexual abuse materials (CSAM).

A 2018 analysis conducted by ECPAT and Interpol analysed one million items depicting child sexual abuse and exploitation and found that where the victim’s gender was recorded, 30.5% were boys [2].

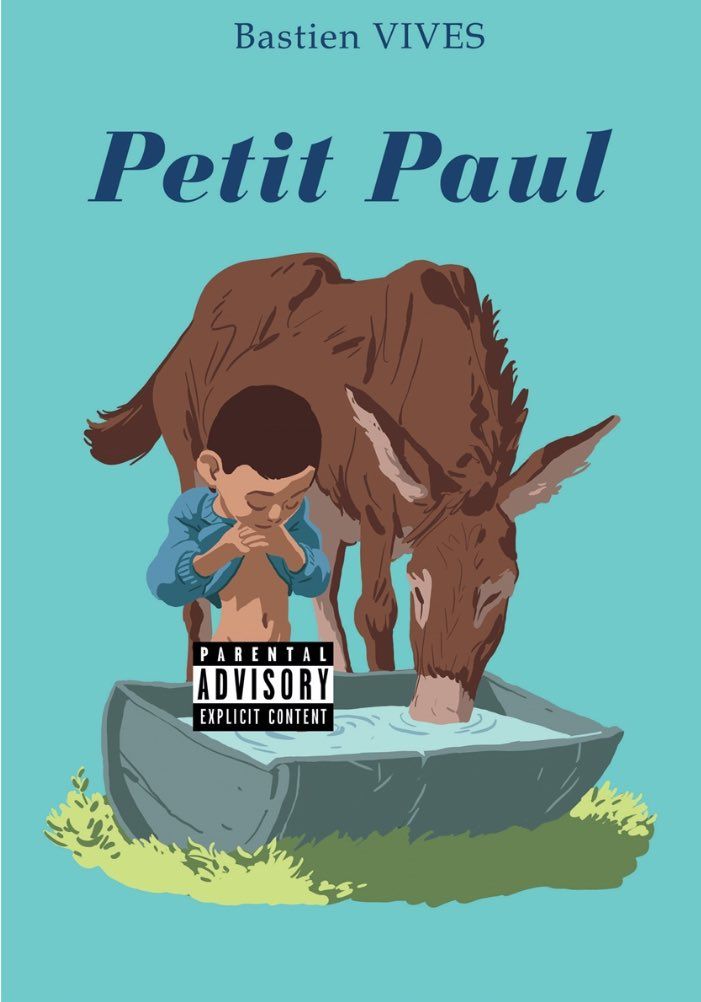

Current laws in Belgium are comprehensive in criminalising various offences related to CSAM, ranging from production to possession. However, the definition of CSAM only covers visual materials such as images or videos and excludes non-visual materials, such as those found in written and audio form.

What support services are available?

From helplines to care centres, numerous support services are available in Belgium and are operated by different organisations.

An estimated 90% of victims admitted to Belgium’s five Sexual Assault Care Centres are female. Although males make up a relatively small proportion of these victims, the data is likely skewed due to issues such as social stigma and gender norms, which contribute to the underreporting of sexual crimes by male victims.

24/7 helplines in Belgium’s three main languages are also available and managed by the various linguistic communities.

However, having numerous parties involved in protecting child survivors of trafficking or sexual exploitation can lead to detrimental effects. The lack of systematic information sharing is a significant obstacle to identifying and supporting potential victims.

What do boys in Belgium need?

Data in the Belgium Boys Report reveals that despite having relatively strong child protection laws, there are gaps in certain legislation that need to be filled to protect children as comprehensively as possible.

Some of the recommendations outlined in this report include:

- Removing the burden of proving lack of consent for minors aged between 14 and 18 years old

- Enhance provisions to criminalise all forms of online child sexual exploitation, including non-visual forms of CSAM

- Future care centres should be established with a gender-sensitive approach that considers the manifestations of sexual exploitation of boys and the specific barriers they face in accessing care and in the recuperation process

Read below the full report.

[1] Myria: 2020 Annual Report

[2] ECPAT and Interpol: Towards a global indicator on unidentified victims in child sexual exploitation material